From Old Florida-style cottages to luxury beach estates, from banks to resorts, metal roofing is cropping up everywhere — for some very good reasons.

By Ryan Reed

When metal roofers sleep, they dream of a place where metal sells itself. Where metal is both hip and traditional, cutting-edge and nostalgic. Where metal’s advantages stand out in high relief, and home owners don’t wonder what the neighbors will think. Where metal has a long history and a brighter future. Whether they know it or not, they are dreaming about Florida.

It’s not that every roof in the Sunshine State glistens metal. Asphalt shingles cover most homes, and tile is the most common alternative. Flat membrane roofs dominate the commercial market. But nowhere, with the possible exception of ski resorts, is residential and commercial metal roofing more prominent. And nowhere do so many architectural traditions and environmental factors converge to make metal a popular choice and appropriate regional choice.

Elsewhere in the country, its promoters trumpet that metal roofing is “gaining acceptance.” Florida is way past that. The boom has been growing for decades, and gets a bump every time a hurricane rips through the state. Twenty years ago, Gulfside Supply’s Del Jackson sold one metal roof a month from his Panhandle office. Now he’s selling three to five — per day. “Based on my company’s figures,” he says, “I’d put the market share of metal in Florida at 35 percent.” Okay, maybe that’s a bit high for the state, but not for some locations. It’s not just a few home owners going for facsimile shingles, or shopping centers sporting green mansards. It’s entire housing developments specifying 5-v crimp or standing seam in their architectural codes. It’s businesses that make metal a signature style. It’s new high-end homes gleaming in Galvalume, older homes restored with tin shingles or corrugated panels. Heck, metal’s practically the law in historic Key West. And since tile, asphalt shingles, and wood shakes are popular here despite climatic handicaps, manufacturers of facsimile products are selling metal versions like hotcakes.

Edwin Guillot spent six months researching roofing materials for his 10,000 sq. ft. residence in exclusive Corey Lake Isles near Tampa. He eventually chose Perfection’s Country Manor Shake, an aluminum shake facsimile, which was then installed by Aluma-Tile Roofers. The owner’s decision was based on Perfection’s lifetime warranty, which no wood shake installer could touch. (Aluma-Tile photo)

The reasons are many. Metal’s reflectance can shave energy bills in Florida’s endless summer more than any other roofing material, as several new studies have shown. With wildfires an increasing problem, metal’s typical Class A ratings and resistance to windblown embers rank high and nothing beats a metal roof for rainwater collection, a practice recently revived in drought-stricken Florida.

Another big factor is algae and mold in Florida’s soggy climate. “Wood shakes are a 10- to 12-year proposition in Florida,” says Aluma-Tile’s Tom McGarr, who installs Classic/Perfections aluminum shakes. “After that, they deteriorate, blow off, or leak.” Asphalt shingles also discolor quickly and need constant cleaning, he says.

Dan John of Scandinavian Profiling, based in Mangonia Park, says his Nordman Tile steel panels sell in large part because, unlike concrete tiles, they won’t grow algae and require minimal maintenance. “Tile isn’t really a wet weather roof,” he adds. “It’s all aesthetics. The only thing keeping a tile roof waterproof is the underlayment.” Asphalt shingles, he says, routinely last half their warranted life in the heat and humidity.

As for hurricanes and other windstorms, metal has earned a reputation for staying put. Everyone in the business has a story about what the last hurricane in their area did to roofs other than metal, and what it did for their business. Beth Folta of Seaside said her all-metal roof community had “a couple corners” turned up by 1995’s Hurricane Opal, while nearby tile and comp roofs were blown off completely. Down in the keys, says Brad Farinelli, it was 1998’s Hurricane Georges that bumped up the metal side of the Bob Hilson & Co.’s business.

Some metal partisans are more emphatic. “Andrew changed everything,” says Consolidated Metal’s Lodell Davison of the 1992 storm that devastated South Florida. “The only thing that stayed on was metal. Asphalt blew off, and tiles became missiles. After that, everyone wanted metal.”

The truth is that manufacturers of most roofing materials have come up with beefed-up versions or fastening systems to hold the roofs down, even to the strict Miami-Dade wind uplift standards. But for decades, according to engineer and insurance industry consultant Do Kim, asphalt shingle manufacturers clung to the assumption that several extra nails would hold their product down in high-wind areas, despite evidence that tab uplift was the weak point. Not until last summer did the Florida code-writing body finally bury attempts to exempt shingles from the same standards as other roofing materials.

In the meantime, tens of thousands of asphalt comp roofs have gone on in Florida that did not meet the higher uplift standards. Which means that, next hurricane, more than fur will be flying — and asphalt shingle’s reputation isn’t likely to improve.

But the biggest force behind metal these days is aesthetics. “People want the metal look,” says Ralph Davis of Tallahassee-based WINCO, who’s roofed hundreds of buildings near the coast. “A lot of folks don’t care about the cost, and they don’t care about longevity either.”

The “metal look” is mostly unpainted or light-colored vertical panels, which have typically accompanied several traditional regional styles: the so-called Cracker style, the fishing village style, the beach style, the Anglo-Caribbean island style. (The bare-metal roof look is in fact popular throughout the coastal South, with several architectural styles.) Galvanized S-tiles and Victorian stamped shingles have also been used for more than a century, particularly in Key West — where many homes still have their original roofs.

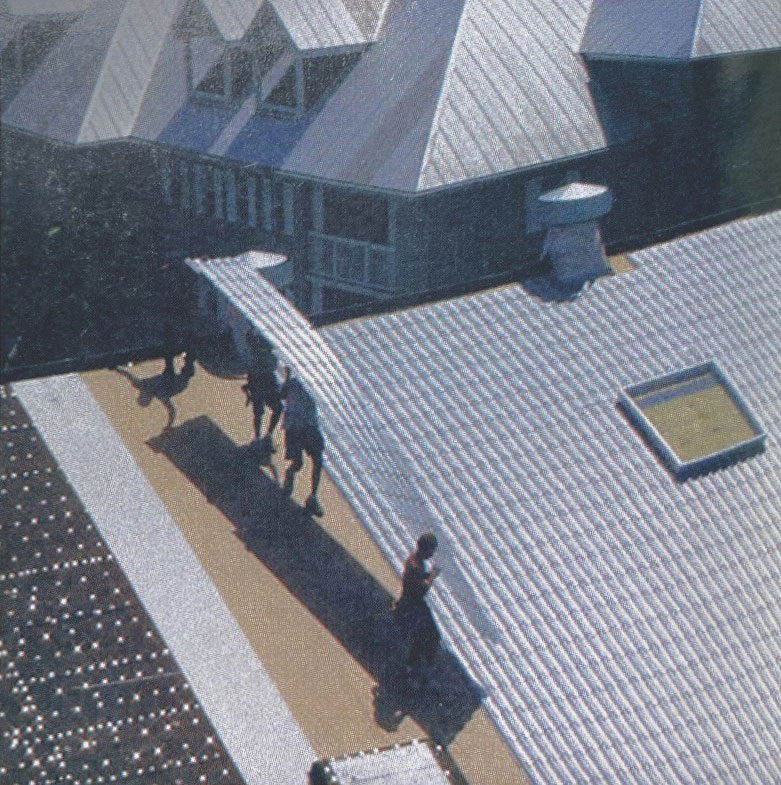

Metal, metal, everywhere. A crew from the Bob Hilson Co., based in Key Largo and Broward, carries a Berridge S-tile panel onto the roof of the historic Clinton Square Market in Key West. Under guidance from the city’s Historic Architectural Review Commission, the company replaced the hundred-year-old galvanized tiles with Berridge’s product, a 24-ga. G90 S-tile painted with a Kynar 500/Hylar 5000 coating in a “Preweathered Galvalume” color. The building in the background is the Key West Hilton, roofed in 5-v crimp.

The style is nostalgic, but still very much a living tradition. Architect Ron Hasse designs homes in careful updates of the so-called Cracker style (the name comes from the whips Florida cowboys used), using all 5-v crimp. Developer Dean Fowler uses 5-v to recreate Florida of the 1890s at his Steinhatchee Landing Resort. A restaurant at WaterColor uses a corrugated roof to evoke a Florida “bayou fish camp” look.

But in the blender of Florida’s come-from-everywhere culture, a hybrid architectural style has emerged that is often simply called “Old Florida”: wood siding, wrap-around porches, high ceilings, and overhanging roofs — always with unpainted or light-colored metal on top.

This is, by and large, metal that’s unafraid to look like metal. In the right place, differentially weathered and even rusty metal can be cool. Jay Maust of Southeastern Metals recently tried to sell a Kynar-coated panel warranted for 30 years, to a project near Ponte Vedra. But the builders wanted one that would weather and rust, just like some of the 20-year-old roofs at the famous Seaside community — and so bought galvanized.

Many Floridians are only dimly of the homegrown metal tradition. Its popularity is seen as something that’s “trickled down” from hotels to shopping centers to residences, or part of a style borrowed from another state. They imagine that tile is the traditional material and metal the newcomer. They’ve got it backwards.

When Americans first moved into Florida in the early 19th century, most homes were topped with cypress shakes; few buildings could support the heavy tiles favored by the Spanish. When galvanized metal sheets became available in the late 19th century, they quickly found their way to the tops of Florida residences. They were easily transported, reflected heat, reliably shed water before there were underlayments, and their light weight allowed for airy, open construction.

Hasse, a professor of architecture at University of Florida, has helped to revive this traditional building style with his 1992 book Classic Cracker: Florida’s Wood-Frame Vernacular Architecture. He calls the Cracker-style home and admirable adaptation to Florida’s climate. Metal roofs were a late but very popular addition.

As the state of Florida’s Historic Property Design Guidelines state, “Metal roofs serve the climate and architecture of Florida well. They eased the weight load on the lightweight, wood frame buildings common to the state and proved durable and comfortable in the harsh climate characterized by copious rainfall, strong winds, and intense sunlight. Relatively cheap and easy to apply, metal roofs appealed to building owners in a state that enjoyed neither great wealth nor large numbers of skilled artisans.”

For decades, metal was traditional and appropriate. The stucco-and-tile pseudo-Mediterranean look gathered strength in Florida only in the 1920s, courtesy of an extravagant self-taught resort builder named Addison Mizner. This Boca Raton/Palm Beach style spread throughout South Florida, and became the state’s “upscale” look thereafter. Eventually many Floridians assumed it to be historically authentic as well.

After World War II millions of immigrants from northern states brought their preferences for ranch-style homes roofed with asphalt or shakes. Metal roofing and the wood-frame vernacular style became an outmoded look, relegated to downscale parts of town. It didn’t help that a lot of cheaply galvanized steel rusted through.

But metal has been coming back for decades. With rising real estate values and a taste for regional style, galvanized roofing is replacing tile as the hip look for many Florida homes. Money is a huge factor. “The market has been growing fast for several years,” says Classic Product’s Todd Miller. “It used to be a really cheap market, but people are building much nicer homes now.”

Environmental sensitivity is playing a role, too, as Floridians look for materials that suit their climate. Haase views his use of metal roofing in this context. “I advocate a home that’s designed as close as possible to nature,” he says. “In Florida, the house shape would induce air movement, and that means cupolas, fans, and porches. You can’t do that with heavy roofs.” Indeed, metal roofs are showcased as an environmentally appropriate material for Florida on several “green” demonstration buildings, including the Florida House Learning Center and the Nature Conservancy’s Disney Wilderness Preserve Center.

It’s not just about reflectivity, lightweight construction, and water collection. “Mold is a huge problem in Florida,” says the Florida House’s Betty Alpaugh. “Everyone has to wash their roofs with chlorine washes. It’s not only time-consuming, it’s another toxic substance that leaches into the water table.” The zinc in their 5-v crimp roof naturally prevents such growths before they can discolor or damage the roof.

Metal’s history in Florida not only creates the foundations of a regional style, it can also sell the product on its merits. “People tell me that their grandmother had a metal roof, and she was poor,” says Jim Beckman of Home Depot Installed, who’s selling Fabwel’s panels. “I tell them their grandmothers were smart to spend extra on a good roof. That grandma’s house often still has the same roof, and that fact can close a sale.”

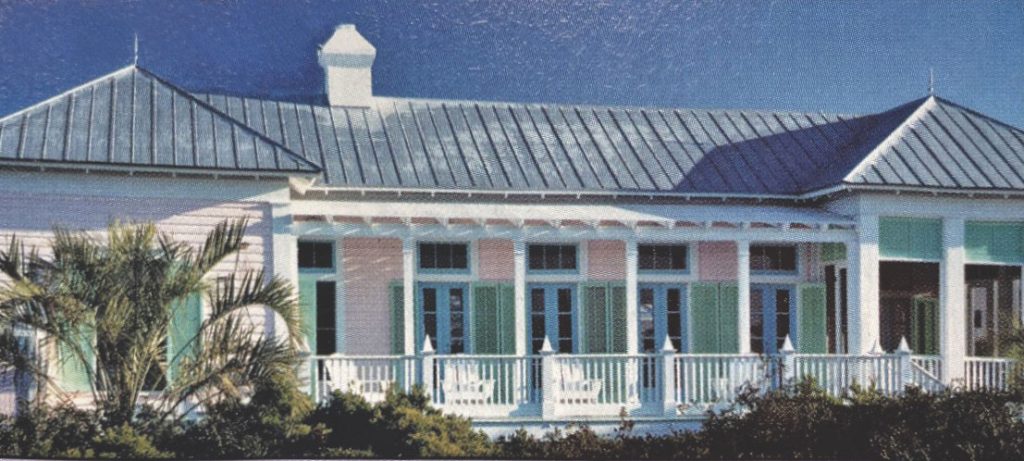

Seasiders don’t insist on unblemished metal. The 5-v crimp roof on this Caribbean cottage, designed by Cooper Johnson Smith Architects, characterizes the casual, real-metal look preferred by many Floridians. But some newer Seaside homes are upgrading to more durable and corrosion-proof panels.

(Photo: George Cott/Chroma)

Metal got a big boost in the early 1980s from Seaside, a world-famous community that specifies unpainted metal on all its buildings. While the innovative, neotraditional planning was done by the firm of Duany-Plater-Zyberk, the metal roofs and frame vernacular style were inspired by developer Robert Davis’ memories of Panhandle beach shacks. Although some Seasiders have gone with more expensive standing seam systems, others take pride in the rustic look of the exposed-fastener systems.

These days the galvanized look is best done with acrylic-coated Galvalume, which has shown greater durability, especially in marine atmospheres. Roofing within a quarter mile of the coast, however, often voids Galvalume’s corrosion warranty. Pre-painted steel adds another barrier to the system — you can even get the metal look with a Kynar/Hylar paint color called “Preweathered Galvalume.”

Some roofers turn to aluminum or stainless steel near the water. Ralph Davis of WENCO rolls a lot of stainless steel, aluminum, and even copper on the coast near Tallahassee. ATAS’ Laf Ried says he sells almost nothing but aluminum for waterfront projects. And corrosion resistance is one of the main selling points for Perfection’s all-aluminum Country Manor Shake, says Aluma-Tile’s Tom McGarr.

At WaterColor, the Arvida development company decided to skip the hip rust look and went with Merchant & Evans’ Zip-Rib in a mill-finished .032 aluminum. The Morin Corporation and Englert also contributed standing-seam panels in aluminum for the project. Even some of the 5-v crimp panels on the cottages are aluminum.

But these are mere details. The point is, metal roofing has achieved a critical mass in Florida: it’s appropriate, it’s accepted, it’s practical, and it’s chic. Whether it’s mill-finished Galvalume panels or metal disguised as tile, wood shakes, shingles, or slate, metal that rusts or metal that doesn’t, it all sells here — and for a long list of reasons.

And it gets better: as Stephanie Smith of Bradco, a major coil and panel distributor based in Tampa, puts it: “The market for metal here is huge, and Florida sets the trends. Then the trends move up the coast.”

But is Boston’s ready for the Key West look? MR

Metal Roofing Magazine was born as a supplement to Rural Builder magazine in 1999. A few more supplements were published in 2000. In 2001 it was elevated to a stand-alone magazine, and today it is over 20 years old.

Our page space is limited, so the article is published here without all of the photos that were published originally. Visit readmetalroofing.com to see more of the residences and businesses that made the upgrade to metal more than 20 years ago.

Reprinted here, in this edition’s “Flashback” feature, is a look at the roofing tradition in Florida, from a 2001 perspective. It’s written by Ryan Reed, a former associate editor of Metal Roofing Magazine.