By Ryan Reed

When Thomas Jefferson roofed the University of Virginia in 1822 in tinplate shingles, he complained bitterly of the exorbitant price a certain Mr. Broke charged for the product: “We were led to it from a belief that it could not be done without the very expensive & complicated machine which he used to bend the tin, which he told us was a patent machine, costing 40 dollars and not to be had in the US … Seeing his machine at work, and how simple the object was, I saw that the same effect could be produced by two boards hinged together.” Jefferson promptly fired Broke and made his own machine for 50 cents, which “did the work as neatly & something quicker than his 40 dollar machine.”

Nearly two centuries later, the business of making metal shingles hasn’t changed all that much. Sure, we don’t use tinplate. And our stamping presses are a bit more complex than “two boards hinged together.” But it’s still an industry of new ideas, questioning old methods, and cutting costs. Every few years, a new entrepreneur comes up with a new idea, a new machine, a new material, or a new way to use an old material.

The metal shingle industry — and by metal shingles we mean overlapping, water-shedding modular panels, whether they’re made to look like tiles, shakes, slate, or other products — is still a young one, full of inventors an innovators and enormous possibilities. “This industry is an infant,” says Joe Zappone, who invented his own shingle more than three decades ago. “We have, what, 8 percent? In Europe, it’s all permanent roofing. That’s where we’re headed.”

Like Zappone, most of those involved are true believers who consider metal a superior product, of significant environmental benefit and value to buyers.

Most also understand the challenges involved in creating a product that is simple to use but designed for durability and weathertightness — and still affordable. For every brash entry into the field, there are as many quiet exits from companies that could not handle the challenges. Jefferson, it might be noted, solved his cost problems — but his metal roof leaked badly and was soon roofed over with wood shingles.

What follows is an overview of metal shingles over the last 200 years, focusing on the products and businesses that have brought the industry to where it is today.

The Tin Shingle Era

Although copper and lead were both used on roofs since the Middle Ages, the first truly affordable metal roofing material was tinplate, which was made by drawing iron sheets through baths of molten tin. In the early 19th century the duller terneplate was developed by drawing iron through a tin-lead bath. Both materials require diligent upkeep and repainting, but otherwise could last many decades.

Roofing shingles have been made from metal for centuries, but until the late 19th century there is little evidence of any shingle manufacturing process — each one was handmade by metal craftsmen (sometimes called brightsmiths). Aside from the University of Virginia, other early metal shingle roofs include the Arch Street Meetinghouse (1804) in Philadelphia, with tin shingles laid in a herringbone pattern, and Hyde Hall (1829) in New York.

Usually edge-folded and installed with clips, simple metal-shingled roofs were common by the 1850s.

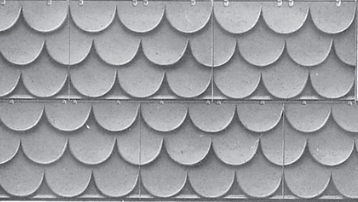

In the late 19th century stamping presses were developed to emboss tin and terne into shingles with distinctive patterns. The most popular of these small, Victorian-era shingles had diamond, fleur-de-lis, or scalloped patterns; seldom were they larger than 9×12 inches. Metal barrel tiles were also made.

From the 1880s to the 1920s, tin shingles proved enormously popular, valued for their light weight, low maintenance, fire resistance, and relatively low cost. Tin roofs had to be kept painted, with red and green the most popular colors.

Although there were metal shingle companies throughout the nation, the area around Wheeling, W.V., was a hotbed. An 1886 article in the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer called the manufacture of “iron roofing” “an industry which is growing to vast proportions in Wheeling.” With three major mills in the area, Wheeling was a natural location for a number of companies: Caldwell & Peterson, William A. List & Co., N.A. Haldeman & Co.

Soon galvanized iron and steel joined tin and terne, but by no means replaced them. It also didn’t change the popular name; stamped shingles of any material remained known as “tin shingles.”

Catalogs from steel companies such as Wheeling Corrugating show that metal roof shingles were marketed to homeowners right alongside other galvanized products, such as ceiling tiles, stove pipe, watering and washing cans, and baking tins. When properly installed, these roofs proved very resilient. But as systems, they weren’t much more than modified stamped ceiling tiles taken outdoors.

Tin shingles were widely popular in their era, but they seem to have survived in certain geographic pockets. In Key West, Fla., tin shingles are often required on historic district buildings to this day, following a tradition begun after a major fire destroyed much of the town early in the 20th century.

Other areas seem to be marked by strong or recent European ethnic descent. Todd Miller of Classic Products notes many such roofs are popular in certain towns in Ohio dominated by immigrants of German heritage. “I assume this is because in Europe, ‘permanent’ roofing has always been the norm,” he says. Their light weight made tin shingles transportable, and they showed up in the west even before the railway made heavier products possible. Allan Reid of Dura-Loc also notes widespread use in Canadian towns such as Simcoe, Ont.

Tin shingles never went out of production, but after the 1930s they increasingly became historic materials. One factor in their demise was the diversion of steel to military uses during World War I, particularly in Canada. Asphalt composition shingles, developed in the 1890s, became inexpensive to make, and the Depression of the 1930s pushed many homeowners into the cheapest alternative. Within a few decades, asphalt shingles had captured up to 90 percent of the residential market.

Aluminum shingles

Even as the tin shingle era was ending, asphalt’s impermanence left just enough of an opening for a new alternative: aluminum. Just decades before considered a precious metal comparable to silver, aluminum was coming into its own as a building material in the 1920s. Its light weight, its superior corrosion resistance relative to galvanized steel, and its ready formability made it an obvious choice for roofing. Aluminum producers, however, initially concentrated on making siding materials.

Not that they didn’t think of roofing. One of the first aluminum shingle roofs was installed on the Pittsburgh Country Club in the 1920s (at last report, it was still in place). The roof presumably involved Alcoa, which was headquartered in the city. But the shingles were hand-made, and there’s no record that the installation was prelude to a product.

Aluminum roofing shingles gradually evolved out of siding products after World War II. In the late 1940s, according to industry veteran Zappone, an aluminum siding salesman named Lou Corder began building stamping presses to produce small interlocking aluminum shingles, about 8×15 inches; some of the half-dozen of these “Alumi-Lock” machines produced are still around, used by smaller regional producers.

Both Reynolds Aluminum and Kaiser Aluminum started designing and developing interlocking shingles in the 1950s, says Classic’s Miller. First into mass production was Kaiser’s Rustic Shingle, introduced in 1959, a 12×24-inch interlocking shake profile. Kaiser also produced the 12×60-inch Rough Shake. These were used both for residential and commercial applications, at first siding and façades, and then tweaked for use on roofs.

Reynolds Aluminum jumped into the fray in the early 1960s with the 12×36-inch Shadow Crest. Both these products were used primarily for commercial applications such as chain stores and restaurants. Classic Products bought Kaiser’s line in 1980 and Reynolds’ in 1987.

In 1972, Alcoa developed the 12×48-inch interlocking Country Cedar Shake for siding applications, adding roofing accessories about two years later. This almost exclusively residential product was bought by Perfection Building Products, a division of Classic Products, in 1995 and became the Country Manor Shake.

Smaller regional companies also produced aluminum shingles, and some continue to do so, but many others have been discontinued. One success story is Zappone, a Kaiser representative who understood the problems of turning siding into roofing products. In 1969 he designed his own aluminum shingle just for roofing, combining features of several other products. Within a decade, inspired by a trip to Europe, Zappone turned his efforts to producing shingles in copper, and his shingle now dominates that niche.

Other designs cropped up from complete strangers to the business. In 1976 Nebraska inventor Richard Reinke, holder of many pivot irrigation patents, looked around for a metal shingle for his home. Finding nothing satisfactory, he bought a 1950 military surplus 50-ton press and created his own corrugated aluminum shingle, now known as the Reinke Shake.

The Stone-Coat Invasion

While aluminum shingle struggled to expand a niche market, an entirely different metal shingle product was being born overseas. The improbable story of stone coating begins in Britain during World War II. Responding to the need to better disguise new corrugated steel buildings from German bombers, the Decraspray Company developed a coal-based sprayable emulsion called Decramastic. When the war ended, it was found that this black coating had virtually bonded with the steel, and could protect it for many years. Contractors began requesting steel sheeting factory-coated with the product, particularly for industrial use.

At the same time, a man named Ben Booth was marketing a similar product that had also been developed as wartime building camouflage: steel panels covered in road tar, then sprinkled with stone chips.

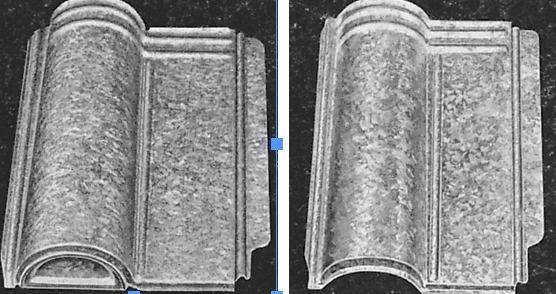

In 1954, a New Zealand metal building importer named L.J. Fisher saw an ad for Decramastic and flew to England to secure the rights to make and sell the product outside England. Not long after he met Booth, and saw the stone-chip concept. As he went into production making Decramastic sheeting, Fisher found that the freshly coated iron sheets bonded to each other when stacked. He first hit on using stone chips to prevent bonding, but soon landed on the idea of marketing a stone-chip covered panel with the Decramastic as the bonder. He bought the rights to use a four-pan aluminum tile profile called Martile, and by 1957 Fisher was producing what he called the Decramastic Roof Tile.

The tile, which used a batten-mounted system, quickly gained acceptance in New Zealand, then Australia; in 1970 the first U.S. offices opened. Improvements were made: the tile was enlarged, given improved side-locks, overglazed to improve chip adhesion, and a “double-drop” method was developed to improve coverage. In 1969 Alex Harvey Industries bought out Fisher, and in 1985 Carter Holt Harvey acquired Alex Harvey. In 1998 Tasman Building Products bought up Carter Holt Harvey’s roofing operations, including the Decra line.

The coal-based Decramastic emulsion went from wartime expedient, to industrial steel protectant, then to stone chip binder; now it’s just a footnote in the history of stone-coating.

Decra’s first successful competitor was Gerard, founded in 1971. By that time many Decramastic roofs were reaching the durability limits of the bituminous coating, and Gerard developed an acrylic resin binder that, while more expensive, proved to have superior longevity. After some criticism, Decra tiles were switched over to acrylic binders during the 1980s. In 1989, Gerard and Decra joined forces in all markets but the United States.

In the American market, stone-coated tile took off in California in the 1980s, with a new red chip that allowed a clay tile look; a shake facsimile product was also developed for the market. California had enormous subdivisions roofed in wood shakes, and by the 1980s these were increasingly targeted by fire officials as fire hazards; many wood roofs also warped and split badly in the arid climate. Stone-coated products proved ideal for reroofing these homes, since the batten-mounted panel could go over the old shakes without tear-off. Single statewide roofing contractor, Cal-Pac Roofing, installed tens of thousands of metal shake and tile roofs over the course of the decade. Gerard (1984) and Decra (1988) both established manufacturing plants in Southern California.

The industry stumbled in the early 1990s after the safety of enclosing wood shakes was challenged, primarily by the tile industry, but Gerard and Decra fought back by establishing industry testing procedures and a firefighting protocol.

Meanwhile, competitors emerged from the ranks. Frustrated by shipping and other problems in Canada, Decra distributor Allan Reid decided to build his own company. He designed the Continental Tile, a profile he considered better suited to North America than the convex pan style, and in 1984 founded Dura-Loc in Courtland, Ont.

Another company emerged from stone-coating’s homeland. Metro Roof Products was founded in 1989 by brothers Ian and James Ross, roofing contractors who were among Decra’s largest installers in New Zealand. The company opened a Southern California plant in 2000. One of its first strokes in the U.S. was to market a battenless stone-coated product that would mimic composition shingles in look and installation; two companies have since followed suit.

Modern shingles

Despite this long history, by the early 1990s metal shingles were still confined to niche markets, especially outside of the West Coast stronghold of the stone-coats. Still, several technical breakthroughs had set the stage for a leap forward: advances in galvanization, the development of Galvalume, improvements in paint lines, and, above all, the creation of fade- and chalk-resistant Kynar-based coil coating systems. Durability could be better assured, and technical issues behind forming and finishing metal made a growing array of styles possible. Metal’s old problems — leaks, corrosion, paint chalk and fade — were receding into the past.

With home prices rising and steel prices low, many felt the time was right for metal to start making a serious dent in composition shingle’s market share.

One of the first to take the challenge head-on was MetalWorks. Prompted by Alcoa’s exit from the market in 1995, Marcus Plowright and Bill Moore-Gough set out to design a metal shingle line from scratch. They began by folding napkins in a Vancouver, B.C., Denny’s restaurant, and a few years later had sold a half interest to Centria and set up shop as MetalWorks.

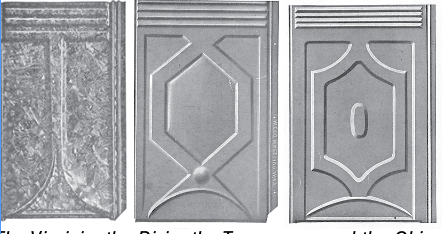

MetalWorks’ steel shingles (initially a wood-grained and a smooth slate) were made with a lighter gauge steel and a lower profile, and installed closer to the deck than other shingles. All the panels are the same size. The emphasis was on simplicity and ease of installation — training is largely confined to a 15-minute video.

“We had to take the power away from the craftsman installer and put it back in the hands of the roofing contractor owner,” says Plowright. “The only way to do this was to make the product easy enough for any asphalt roofer to tackle, with no special tools or training.”

The company moved aggressively to acquire the kind of widespread wholesale distribution that asphalt shingles enjoy.

Other companies launched or upgraded products. Classic introduced a shake product with a textured, powder-coat finish. Dura-Loc introduced shake facsimiles and direct-to-deck tile and slate panels. ATAS picked up a unique diamond shingle. Many companies began offering their shingles in copper and titanium-zinc. In 2000 Walter Hauk licensed the Zappone design to produce a ground-breaking colorized stainless steel product, the Millennium Tile.

But most of the new products have been designed to mimic the look and installation ease of asphalt composition shingles — a sign that metal can fight the dominant material on its own aesthetic ground. Classic Products came out with a low-profile shingle facsimile out of aluminum, the Oxford Shingle, in 2001. Wierton Steel and ATAS teamed up to produce the Advanta Shingle. National Steel, struggling with bankruptcy, announced it was developing a steel shingle in the late 1990s, and finally brought out the Centura Shingle in 2002, distributed by Georgia Pacific. Several stone-coated manufacturers also launched battenless shingle products that both look and install more like “dimensional” composition shingles.

The 1990s also saw the organization of the Metal Roofing Alliance, which aimed to take the gospel of metal roofing directly to homeowners. While hardly limited to modular products — most residential metal roofing was, and remains through-fastened panels or standing seam-style panels — the appearance of affordable, mass-produced metal shingles, shakes, and tiles was certainly a necessary condition for the marketing effort.

And of course, in 2000, metal roofing truly came of age with the launch of the first magazine devoted to the topic.

Over the past several years, manufacturer-members of the MRA have seen double-digit sales growth annually. The explosion of the metal shingle business hasn’t gone unnoticed. In 2000, roofing giant Owens Corning bought the U.S. rights to the Vail Shingle, an intricately folded shingle made in copper and painted steel developed for use on upscale projects around Vail, Colo. The product was folded into the company’s high-end MiraVista line, which ultimately included standing seam panels as well as synthetic slate and shake products.

The prospect of a giant corporation pushing metal roofing sent both alarm an excitement through the industry. The episode proved short-lived, however — Owens Corning abruptly dropped the entire MiraVista line in the fall of 2002. The reasons were never given, but no doubt included performance problems with the line’s synthetic materials, the Vail shingle’s production costs, and the division’s short financial leash, due to the company’s asbestos-related bankruptcy status.

Some doubt whether a giant company like Owens Corning can properly distribute a metal product, which requires constant education, training, and support. “They tried to market it like comp,” says Zappone. “Metal requires more finesse. You have to find guys who will be proud of what they’re doing.” This, he says, is why small companies have dominated the metal shingle business.

Others think the big company’s adventure may be a taste of things to come. As stone-coated veteran Peter Croft reported being told by a composition shingle maker, “You guys develop the market, then we’ll come in and buy you up.” MR

Current Trend: Elevated Performance

Robin Anderson, Technical and Strategy Development Manager for Westlake Royal Roofing Solutions™, has this to say about the metal shingle market.

Q: How have metal shingles (and/or the metal shingle market) changed over the last 20 years?

A: The past two decades have brought a significant emphasis on energy efficiency and product sustainability. Builders and design professionals are looking for roofing materials that are manufactured to achieve elevated performance goals. Metal shingles systems have been developed to further provide a greater thermal performance than have been made available in the past; systems that utilize Above Sheeting Ventilation (ASV) and enhanced solar reflective characteristics are now more widely sought after as the desired solution to these performance needs.

Q: What are consumers currently looking for?

A: Consumers have been asking for roof coverings that provide not only beauty to their properties, but that also help reduce energy bills and provide enduring protection. Metal shingle solutions that provide ASV, insulation performance, and reflective coatings are in wide demand. Because of the ever-changing climate conditions in various regions, consumers are ultimately looking for metal shingle solutions that provide protection from the most severe environmental elements, including fire, wind, rain, and hail impacts.

Q: How have the manufacturing process and/or coatings changed over the course of the last 20 years?

A: With efforts for constant improvement, the chemistry of the finishes has been enhanced for greater resistance to the harshest of environmental elements, with greater flexibility, better adhesion of the finish to the metal substrate, and improved resistance to color loss and fade. On the aesthetics side, we’ve given the end user a more consistent design and longer-lasting product.

Q: What is your prediction for the future of the market?

A: It is likely that we will continue to see an ever-increasing need for higher-performing systems that are designed to protect and improve the structures to which they are installed.

How Shingles Have Changed Over the Last

20 Years

Now that you’ve read about the history of metal shingles, you’re probably wondering, “How are metal shingles — and the metal shingle market — different than they were 20 years ago?”

Todd Miller, Isaiah Industries, brings us up to date with this brief Q&A session.

Q: How have metal shingles (and/or the metal shingle market) changed over the last 20 years?

A: You know, metal shingles have gained market share but probably not as rapidly as vertical seam metal roofing has. This is largely due to the onset of more regional and even jobsite fabrication of standing seam roofing and other vertical panels. EDCO has been a significant entrant into metal shingles, as have been ProVia and Vic West. One thing that has really driven metal shingles to a new level is the development of “print coat” paint finishes that allow more than one color to be on the panel. This has especially developed the production of products that even more closely resemble wood and slate. We also have seen Certainteed and Quality Edge come and go from the production of metal shingles.

Q: What are consumers currently looking for?

A: You know, I think homeowners today just want the durability of metal roofing and also the ability to place a long-term solar array on top of their roof. Beyond that, they look for the metal roof that best suits the style of their home and its surroundings.

Q: How have the manufacturing process and/or coatings changed over the course of the last 20 years?

A: Not a lot has changed other than the increased use of print coats as mentioned earlier. Production still remains fairly similar to how it’s always been.

Q: What is your prediction for the future of the market?

A: One struggle for metal shingles has been a lack of installers. I am pleased to see that MCA has teamed with NRCA for developing a ProCertification test for metal shingles. I do hope that, 40 years from now, most professional roofing crews will be well versed in installing metal roofs of all types. Slowly, we are making progress toward that end.

Q: What else would you like to share?

A: One area of significant research right now in regards to the energy efficiency of homes has been thermal breaks. Metal shingles feature their own integrated thermal break and I think that will gain more recognition in coming years.