By Linda Schmid and Ray Smith, AppliCad

If you talk to people in the roofing industry, the buzz is that people are moving to metal roofing. Certainly that seems to be borne out by the statistics: According to the Dodge Report, the share of residential metal roofing in the United States has risen from 12 percent in 2019 to 17 percent in 2021, quite a change in only three years. Depending on whose statistics you go with, estimates are given that 75 to 80 percent of residences in the US currently have asphalt shingle roofs.

The story is different in some other parts of the world. In Australia, for example, metal is the most popular roofing material. According to Ray Smith, CEO of AppliCad, Australia’s market is just the opposite of the U.S. with about 75% of residences installing metal roofs and over 90% of commercial buildings using metal roofing. Metal is also widely used as an option for wall cladding on residential and industrial structures too.

Differences in the Way the Roofing Trade Developed

Smith believes there are a couple of different reasons for this, the first having to do with how the construction industry developed in both countries. European settlers brought European construction with them to Australia, according to Smith. They created open rafter roofs with battens or purlins along with clay or concrete tiles. When more accurate ways of estimating metal jobs came along, people moved to metal. In Australia, this roof type is more cost-effective, and Smith says that in most areas, Australia doesn’t get such extreme snow that might make a roof deck with waterproof membrane necessary.

Of course, the early settlers in America were European also, and when they came, many did use the old methods, creating clay tiles or using slate, but the most plentiful resource they found was wood. With the amazing, largely untouched forests that stretched across great swaths of the continent, it was inevitable that wood would become a staple in American construction, and that meant many wooden shakes for roofing. Eventually, America started moving away from wooden roofs due to their tendency to catch fire. It was also about this time that asphalt was developed as a by-product of the petroleum industry, and asphalt seemed durable, less of a fire hazard, cheap, and easy to install. Eventually asphalt shingles became the standard in the US.

Metal has always been used on Australian roofs, but until more accurate and efficient ways of estimating a job were developed, the majority of Australian roofers were working in concrete tile and clay tile 20 to 30 years ago. The combination of longevity, sustainability, and price were the compelling reasons, not to mention that with concrete and clay tiles the rafters were required to be much closer together to accommodate the load of tiles, adding to labor, resources, and of course, cost.

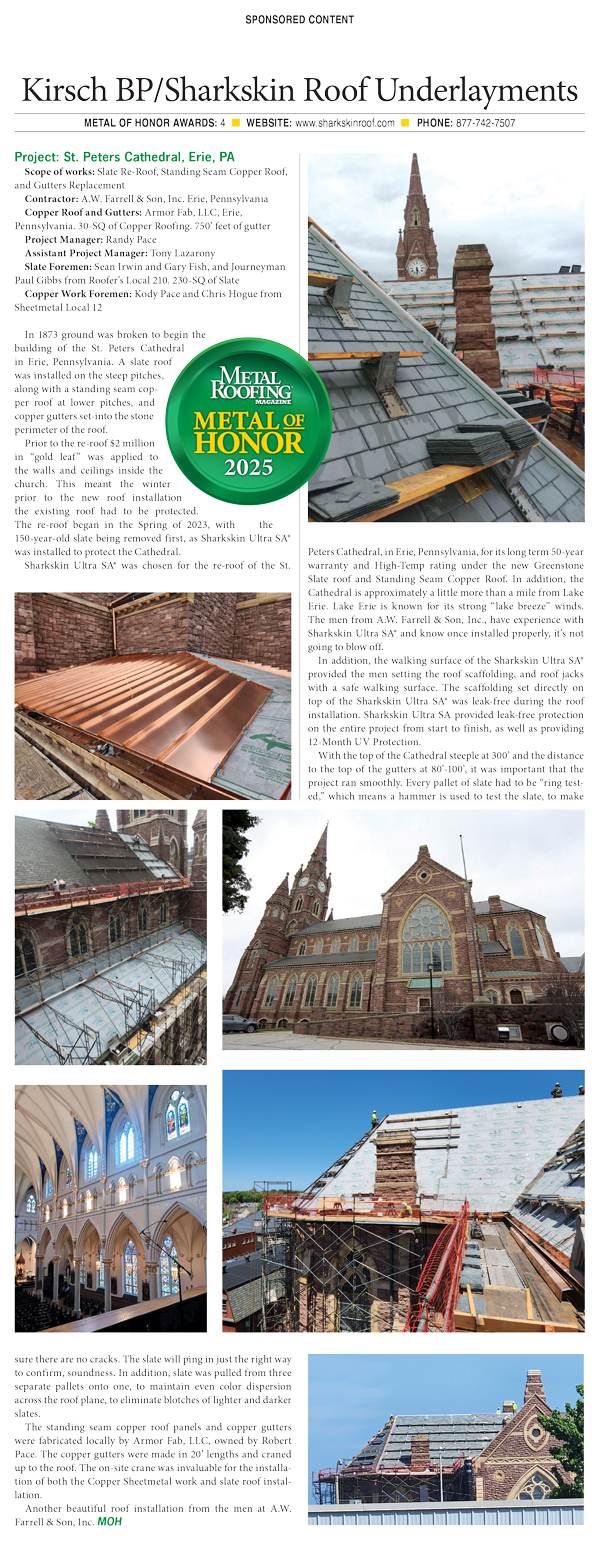

Commercial

roof & wall, trapezoidal profile.

Photo Courtesy of Riverlea Group, NZ

Commercial roof, corrugated, painted profile. Photo Courtesy of AppliCad, AU

Corrugated residential roof. Photo Courtesy of Wall Roofing, NS

Corrugated residential roof. Photo Courtesy of Walls Metal Roofing, NS

Corrugated Residential Roofing. Photo

Courtesy of the Riverlea Group, NZ

Corrugated residential roof. Photo Courtesy of Walls Metal Roofing, NS

20-year-old corrugated residential roofing. Photo Courtesy of AppliCad, AU

Corrugated residential roof installed 75 years ago

in Australia. Photo Courtesy of AppliCad, AU

Which Roofing Is Better?

As is usual with a paradigm, each group believes their way is better. Metal roofing systems last longer than the traditional asphalt shingle system, so in the Australian viewpoint, Americans pay to have their homes re-roofed only to come back in a dozen years or so, tear it off, and do it all over again. Australians expect their roofs to last for the lifetime of their home. Many Americans, on the other hand prefer to pay for the lower-cost asphalt shingle roof, especially if they are unsure how long they will stay in their home. Curiously, you would expect that this affects the resale value, but that doesn’t figure in any of the discussions that Smith has had in his travels across the US.

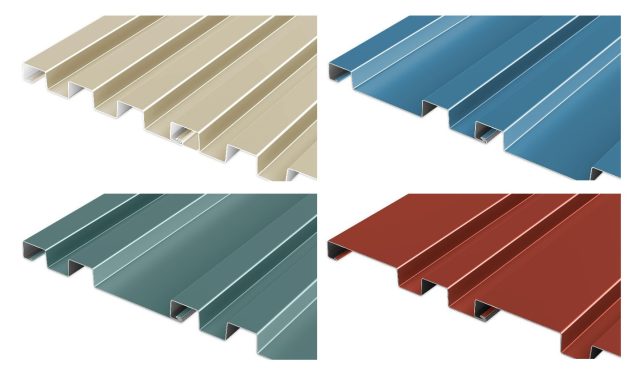

Australians and Americans have different aesthetic ideas about roofing as well. Americans have become attached to the look of asphalt, while, in general, Australians prefer metal roofing. Further, when Americans opt for metal, they usually choose standing seam, while Australians prefer the look of corrugated metal. A corrugated metal roof system is cost effective, in part due to the framing described above, and it’s less expensive to install, largely because of labor. One corrugated panel is equal to 2 1/4 to 3 standing seam panels in width, so the installation is completed more quickly. The metal is usually 0.48 BMT steel (Base Metal Thickness), approximately 26 gauge from Bluescope Steel® with their Colorbond® paint finish system.

Many American roofers say that through-fastened metal roofing does not belong on a house because, in essence, you take a water-tight surface and punch a bunch of holes in it. Smith acknowledges that this is true, but he says that there are many examples of corrugated roofs that are still going strong after 60 to 70 years. Much of longevity, of course, has to do with the quality of the components as well as the workmanship of the roofer and the level of maintenance by the building owner.

Accurate Quoting

Smith recognizes that while there is merit in every roof system, the key is to ensure that the building owner is adequately informed and understands the limitations of each system — all roof systems will work as designed, so long as they are well-built. In considering what roofing material to install there are three primary considerations as suggested above — the “curb-side appeal,” the longevity of the materials selected, and the cost, and this should include costs relating to long-term care and maintenance if appropriate.

“A roofer getting into metal is well advised to have an accurate quoting system that creates precise cutting lists that can be checked and verified, and to order panels from a factory that specialises in making panels and trims. The vast majority of metal roofing systems in Australia, New Zealand and Africa are roll formed in a factory to very exacting standards. It is the method of accurate quoting and minimising waste that has contributed to the growth of metal roofing in Australia from about 20-25% 20 years ago to the numbers we have now.”

“Indeed, even the trims are roll formed increasing accuracy and reducing cost — roll formed trims (ridge and hip caps, gutters, fascia trims, etc.) are cut to length up to a maximum length at cents per foot, whereas trims made in a press-brake will be dollars per foot to fabricate. Cut-to-length trims reduce the number of joins and improve the overall appearance of the completed job,” Smith explains.

Different Educational Requirements

Australian roofers are required to become certified “roof plumbers,” which is a four-year course. In fact, everyone involved in the building industry needs to become certified and the builder (aka a contractor in America) is responsible for the job that everyone does so he is unlikely to hire an uncertified sub-contractor.

Smith said that with traditional asphalt shingles, if a roofer runs short, he can simply go to the nearest home builders’ supply store and buy a few more shingles. However, if you are working in metal, you need to be more accurate; you can’t just run out and buy more. If the correct length is not supplied, you can’t stretch it and such mistakes quickly become very expensive mistakes that can ruin your business for good.

There is a growing trend for roofers to overcome this problem by buying their own portable roll former and making panels on site as they go, however they must still order the correct amount of coil to complete the job. Smith questions the merit of on-site roll forming of metal roof panels for every job. Is this the most cost-effective method? He explains that you must factor the cost of an expensive machine sitting in a paddock for the duration of the job, and the wear and tear on the machine, hauling from job site to job site. Smith has several customers who recognize these issues and have their portable roll former set up in a factory where they are running multiple shifts creating roofing panels for their installers and customers. The machines never stop making panels.

The key to success with this process is accurate cutting details for panels and trims, whether you use a portable roll former or order from the shop, so we’re back to the point made above about accurate quoting.

As Smith understands it, portable roll forming machines were originally developed in Germany where roofing of all types is installed by tradespeople formally trained and with years of experience to be considered a qualified roofer. In the hands of such qualified trades, the portable roll former simply made them more efficient. They already know how to install standing seam profiles and more importantly, make the roof waterproof. Simply throwing panels at a plywood deck doesn’t make a roof waterproof. The ‘devil is in the details,’ and this has never been more appropriate as used to describe the finishing at the edges of a roof. Poor installation of the trims and edge assemblies is generally where most metal roof failures occur, regardless of the profile. So, buying a portable roll former does not actually solve any problems if it is not used by people who know what they’re doing and why, Smith said.

There is no nationwide certification course required of roofers in America. The NRCA has many programs that are well recognized nationally as established “best practices,” as does the MBMA and MCA, but they are not “standards” and there is no governance of adherence to best practice. Maybe the real issue, Smith said, is that local building authorities (state or county, whoever — the AHJ — the Authority Having Jurisdiction) don’t insist that the guys doing this work can demonstrate that they know what they’re doing, and the poor quality of many reflects badly on the best quality of a few.

Many roofers are very experienced and can put up an exceptionally good roof, but if an asphalt roofer decides to enter the metal market without the appropriate training, will the integrity of the metal industry be maintained? Smith believes that the best way to ensure standards are maintained is to require compulsory training and nationally recognized certification as they have in Australia, New Zealand, and the UK. Having said this, one common theme in all the places Smith has visited around the world, is this: If you are the owner of a residence that has a poorly installed roof system, for whatever reason, getting things fixed is very difficult.MR

Roofing In Nova Scotia

Similar to roofing in the United States, metal is gaining traction in Nova Scotia. Josh Deal of Walls Metal Roofing said that in 2013 his company added metal to their residential roofing options, and they have seen it double year over year.

“Ten years ago, metal roofing was mainly an agricultural product,” Deal said, “and asphalt was the main choice for residential. Now metal is more accepted.”

As it is in many other geographical areas, price is the main reason that many Nova Scotians stick with asphalt roofing. Deal said that in the last few years, when he and his team have gone to home shows, they find that they can be very competitive with asphalt on larger jobs because they make the panels and trims in-house, plus their crews are highly experienced and efficient.

Perhaps that economy of scale is the reason that metal roofing is growing more quickly in the commercial and the agricultural markets, while it grows more slowly in the residential market. Deal said the region is largely filled with people of moderate income, fishermen, small farmers, and lumbermen, and they mainly live in small bungalows. Tile or resin are uncommon, though occasionally you come across a flat roof, and approximately one house in fifteen is metal-roofed. Deal said that once one person in a neighborhood gets a metal roof, you usually see a few neighbors follow suit so that there are clusters of metal roofs.

Most people live within an area that exposes their homes to high wind and salt spray, so that is usually a concern. The industry standard for metal roofing in the region is 28 gauge, but many use 26 gauge metal with an SMP paint system. Exposed fastener is more common for financial reasons; standing seam and other modern profiles cost more.

There are no certification or educational requirements for roofers. Most people learn on the job, Deal said. He doesn’t see this as a problem; he said you can tell pretty early on who has potential and who is not going to make a good roofer. •

Roofing In New Zealand

Stephen Thomas, Product Development Manager of the Riverlea Group, New Zealand, said that the roofing practices in New Zealand vary from American practices, and even from Australian practices, although New Zealand and Australia are relatively close. Lightweight steel roofs are the most popular roofing because of the country’s geography. Earthquakes are a concern, and most of the populated areas are located close to the coast making corrosive airborne salt a concern as well. Heavy roofing, such as concrete and clay tile is no longer as popular, and, he said, asphalt shingles are uncommon due to their reputation of having poor durability and susceptibility to New Zealand’s high UV ray levels.

“Most steel roofing coil is supplied by just two companies in New Zealand, and while imported coil from Asia is often more competitive,” Thomas said, “it has a relatively small market share.” The local steel is made from iron-rich marine sands, strengthening the steel so that nominal G550 (550 MPa) material is often actually 650 to 750 MPa. The sole local smelter is also planning on moving from AZ coated steel to AM coated steel, with about 3% Magnesium, which will provide greater corrosion resistance with less metallic coating. The smelter is currently working to become more environmentally friendly, partnering with the government to add an electric arc furnace so they may process more scrap steel.

A variety of roofing profiles are popular, including trapezoidal profiles. Corrugated panels are very commonly installed on residential builds, and standing seam is used mainly for residential roofing. The most common coil size is a 940mm (37”) coil, 27 gauge, high tensile (G550) material for residential, rural, and small commercial developments. For large commercial developments, 1219mm (48”) coil in 25 gauge is by far the prevailing choice.

Dripstop and other similar products were introduced about five years ago and are becoming an accepted alternative to a separate underlayment.

There are no specific requirements to become a roofer in New Zealand, though Thomas said that many employers prefer to hire workers who have a certification or are working toward one. •